Listen to the album:

From Disappearance to Diadems: Fabien Polair Unearths a New Peace

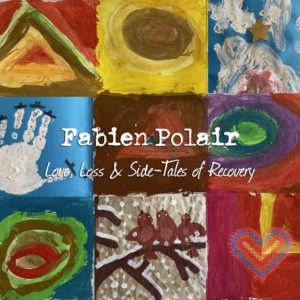

Fabien Polair, a figure who seemed to have slipped into the ether, emerges from a seventeen-year silence not with a whisper, but with a deeply resonant chord. Love, Loss & Side-Tales of Recovery, his long-awaited successor to 2008’s Crossroads, Middletown, isn’t merely a return; it’s an excavation, a patient unearthing of a life lived, a chronicle etched in melody and raw, reflective verse.

The intervening years weren’t a void, but a chrysalis, and Polair, like a cicada emerging after a long slumber, carries the weight and wisdom of that hidden metamorphosis.

The album’s very genesis is framed by its opening gambit, “Let’s talk about being late,” from Momentum. It’s a line delivered not with apology, but with a wry acknowledgment of the expansive gap since his last full-length. This isn’t lateness, however, so much as an intentional retreat, hinted at later in Strange Times with the disarmingly candid admission, “I need to keep looking after our family.” The London-centric anxieties of Crossroads, Middletown feel like a distant echo, a ghost laid to rest by the prophetic calm of Settle Down. Polair has indeed settled, finding love, building a family, trading the urban hum for the sun-drenched quietude of the South of France. His SoftSuns side project offered fleeting glimpses, but Love, Loss & Side-Tales of Recovery is the full, unvarnished portrait of this lived experience.

Musically, the album picks up the threads of its predecessor, particularly in the Americana-tinged embrace of Momentum, where harmonica wails and pedal steel swells conjure the dusty highway landscapes of Neil Young or the Jayhawks. Yet, Polair is not content to simply retrace old footsteps. This ten-track journey sprawls into new sonic territories, guided by the triptych of its title: love, loss, and the arduous, often circuitous path of recovery.

Momentum, beyond its opening quip, spirals into a tempest of disbelief and stubbornness, building an intensity that mirrors a spirit pushing against the current. The album’s first single, Sweet Christmas Dream, however, offers a tender counterpoint. It’s an ode to domestic bliss, a shimmering landscape painted with chimes and angelic choirs, where Polair’s voice, once tinged with a restless melancholy, now conveys a profound, almost defiant contentment. The seventeen years, he suggests, were simply “life”—a sprawling, messy, beautiful thing that demanded his full attention.

The album truly takes flight in its more dynamic shifts, particularly with Diadems and Experiment.

Diadems sheds its initial acoustic skin for a gloriously noisy finale, recalling the shimmering, feedback-laden pop of 90s shoegaze acts like Ride. Its central motif of “tidied up my stones, all that’s left is diadems” speaks to an enduring friendship, a theme Polair has woven through his work since his early days with UNaware.

Experiment, meanwhile, unfurls with arpeggiated delicacy and a bassline that conjures the gothic introspection of The Cure’s Pornography, before erupting into a Pixies-esque maelstrom of swirling bass and distorted guitars. Polair’s vocal delivery on “Life’s an experiment” is raw, unvarnished, a guttural expulsion of the pain and profound experience that inform his reflections on life’s labyrinthine paths and the hard-won pursuit of peace.

Polair also revisits his more politically charged past with Nothing, drawing lyrical fire directly from the unsettling pronouncements of Donald Trump. It’s a stark reminder that while his personal world has found solace, the broader world remains a source of unease, a thread connecting back to the commentary of 2006’s Circumstances of the Present World.

But it is in the album’s quieter corners that Polair’s renewed serenity truly shines. Little Weight, with its haunting piano, evokes a vast American road trip, a solitary journey along Route 281, while Strange Times and Desperate Hours, with their classical guitar flourishes, echo the hushed gravitas of Leonard Cohen or the quiet introspection of Kings of Convenience.

The album culminates with Sunshine, a pure, unadulterated love song. Its jangly ukulele and bouncy riff are a testament to Polair’s newfound optimism, a declaration of “I’ll keep that sunshine with me now, and for the rest of my life.”

Love, Loss & Side-Tales of Recovery is a testament to the fact that some artistic endeavors need time to ripen, to gather the textures of a lived experience before they can truly blossom. Fabien Polair returns not as a relic, but as a seasoned sage, his voice imbued with the wisdom that “one day you fall, the next you float,” and the profound peace of knowing he is “finally home.”

This isn’t just one of his best albums; it’s a profound statement of renewal, suggesting that this long-awaited return is merely the beginning of a vibrant new chapter.

Missed Turns and Pedal Steel Dreams: Polair’s “Momentum” Still Burns Bright

In the sprawling, often-bleak landscape of mid-aughts indie-folk, where every other singer-songwriter seemed to be channeling some combination of Sufjan Stevens‘ pastoral whimsy and Bon Iver‘s cabin-fever introspection, Polair’s Momentum emerges not as a lost relic, but as a surprisingly sturdy time capsule. Penned in 2008, smack dab in the middle of his Crossroads, Middletown tour, it’s a track that wears its Americana influences like a well-worn denim jacket — familiar, comfortable, and a little bit threadbare in the best possible way.

The arrangements here are precisely what you’d expect: folk guitars strumming with a casual confidence, a harmonica sighing somewhere in the background, and that tell-tale pedal steel weeping mournfully like a lonely ghost at a forgotten crossroads. It’s a sound that evokes dusty highways and empty diners, a soundtrack to existential dread served with a side of lukewarm coffee.

Lyrically, Momentum dives headfirst into that particularly sticky brand of personal reckoning Polair seems to excel at. We’re talking about the kind of past love affairs that linger like a bad hangover, where the regret isn’t just about the breakup, but the entire missed damn train. “Let’s talk about being late, out of place, miss the momentum” isn’t just a line; it’s the whispered confession of anyone who’s ever looked back and realized they fumbled the bag spectacularly.

The verses are a masterclass in disillusionment, tackling the bitter pill of hard truths: “It’s not too hard to admit / It’s just tough to swallow / When everything you believed true / Is just daydreams overgrown.” If you haven’t felt that gut punch, you’re either still blissfully naive or you’ve successfully repressed a significant portion of your emotional history. There’s also the Sisyphean struggle to let go, articulated simply as, “It’s just a case of remembering / You’ve got to let go.” Easier said than done, pal.

And then there’s that chorus, a mantra of persistent, perhaps pointless, effort: “Yet you try / To do it yourself / To do it your way / Though there’s no point in even trying.” It’s the rallying cry of every person who’s ever stubbornly clung to a sinking ship, convinced their sheer force of will could somehow bail it out. The track’s emotional crescendo arrives with the raw, desperate plea: “Is there still room to breathe / In this inferno? / When your life burns on both ends / There’s nowhere left to go.” It’s less a question and more a choked gasp, a vivid image of being trapped in a self-made purgatory.

Momentum is the opening salvo of Polair’s new album, Love, Loss & Side-Tales of Recovery. And while the recovery part might still be a work in progress, this single makes a strong case for revisiting the moments when things irrevocably went wrong. It’s available now on all your preferred streaming platforms, presumably ready to soundtrack your next bout of melancholic reflection.

Diadems: A Familiar Echo, A New Resolve

One might forgive a moment of déjà vu upon encountering Fabien Polair’s Diadems. After all, its skeletal structure dates back to his UNaware days, then lurking under the decidedly less regal moniker of Call It A Call. And while the lyrics have been entirely overhauled – a smart move, perhaps, given the often-harrowing journey of re-encountering one’s youthful artistic dalliances – the musical lineage remains strikingly apparent. We’re talking noisy pop and shoegaze, a sonic palette that immediately conjures up the ghost of Ride, though perhaps less prone to dissolving into a puddle of reverb and more inclined towards the sort of modern, laconic introspection Bill Callahan has perfected. Imagine, if you will, the latter’s “My Friend” if it had spent a gap year in a particularly echoey practice space with a fuzz pedal for company.

moniker of Call It A Call. And while the lyrics have been entirely overhauled – a smart move, perhaps, given the often-harrowing journey of re-encountering one’s youthful artistic dalliances – the musical lineage remains strikingly apparent. We’re talking noisy pop and shoegaze, a sonic palette that immediately conjures up the ghost of Ride, though perhaps less prone to dissolving into a puddle of reverb and more inclined towards the sort of modern, laconic introspection Bill Callahan has perfected. Imagine, if you will, the latter’s “My Friend” if it had spent a gap year in a particularly echoey practice space with a fuzz pedal for company.

Where Polair’s previous work, particularly on Crossroads, Middletown, often wallowed in a kind of underlying disillusionment – a feeling as comforting and pervasive as a damp British summer – Diadems signals a discernible shift. This isn’t the sound of someone succumbing to the encroaching gloom; it’s the sound of someone actively, almost defiantly, pushing back. “Bad old fears don’t disappear / We try to hide them, they can’t be buried,” he admits, with a frankness that suggests he’s long since tired of the psychological equivalent of sweeping dust under the rug. But then comes the retort, a clenched-fist declaration: “I’ll push my demons out of reach / And make anxiety go away.” It’s less a whisper of hope and more a rallying cry, the kind you might hear just before someone finally gets off the sofa and does something about it.

And what, precisely, is this newly discovered wellspring of fortitude? Gratitude, it seems. Not the saccharine, Instagram-filtered variety, but a genuine, hard-won appreciation for the human connections that tether us to sanity. “My friends, your love is all around me / I’m so blessed for all these years by your side,” he sings, and for once, it doesn’t sound like a line lifted from a particularly earnest greeting card. There’s a recognition of mutual burden-sharing: “I know you always saw through the cracks / Help carry that solitude so heavy and vile.” It’s a testament to the quiet, unsung heroism of simply being there for someone.

Ultimately, Diadems emerges as an optimistic declaration, a heartfelt, albeit slightly world-weary, nod to the enduring power of friendship in the face of life’s interminable crapness. It’s track three on Love, Loss & Side-Tales of Recovery, an album title that suggests Polair is still very much in the business of unpicking the messy bits of existence, but perhaps, this time, with a lighter touch. You can find it now on all your usual streaming platforms, should you wish to bathe in its resilient glow.

Little Weight: The Weight of Unspoken Histories

Polair’s Little Weight arrives less as a song and more as a whispered artefact, a sonic excavation of a seemingly innocuous encounter in Mexico, 2009. From its first delicate notes, the track establishes a liminal space, a sort of acoustic purgatory built from the haunting resonance of piano chords, the faint, almost imperceptible rustle of maracas, and the intricate, melancholic dance of a classical guitar in a bossa nova cadence. It’s a composition that speaks to the quietude of introspection, drawing parallels not just to the meticulous minimalism of Kings of Convenience, but to a deeper tradition of art that finds its profoundest statements in the unsaid.

guitar in a bossa nova cadence. It’s a composition that speaks to the quietude of introspection, drawing parallels not just to the meticulous minimalism of Kings of Convenience, but to a deeper tradition of art that finds its profoundest statements in the unsaid.

The true genius of Little Weight lies in its narrative obliqueness. It doesn’t tell a story so much as it presents a series of meticulously observed vignettes, hinting at the deeply human phenomenon of unacknowledged burdens. The lyrics, sparse yet loaded with implication—“She’s got a weight on her shoulders / She won’t tell, won’t say a word / Just ask me / To take her to the river…”—evoke a figure who carries a silent history, a burden so internalized it has become part of her very being. This is not the weight of trauma, perhaps, but of resignation, of a stoicism born from repeated engagement with an intractable reality.

The yearning for escape, articulated in the vivid, almost cinematic imagery—“Take me down 281 she said / Stop in dusty motels in Red Lake / Follow Grande River / Cross the border, disappear / And never look back”—is a familiar human impulse. It speaks to the desire for tabula rasa, a shedding of the self in pursuit of an elusive freedom. Yet, Polair, with a masterful, almost philosophical turn, subverts this longing in the track’s denouement.

The revelation that “the little weight on her shoulders / Is worth everything to her / So she won’t vanish / No she won’t vanish” transforms the initial lament into a profound affirmation. This is not simply acceptance, but a recognition of the indispensable nature of one’s own particular burden. It suggests that identity, perhaps, is not merely forged in liberation, but also in the quiet, unyielding commitment to the very things that tether us. Polair’s sparse instrumentation, then, ceases to be merely aesthetic; it becomes a conceptual framework, amplifying the profound paradox at the heart of the human condition: that sometimes, the most precious parts of ourselves are those we’ve been carrying all along.

Little Weight is a poignant rumination on resilience, not as triumph over adversity, but as a steadfast, almost sacred, communion with one’s own irreducible self.

Sunshine: Two-Bit Pop (Worth Its Weight in Gold)

Under three minutes, precisely timed, this track shoves the idea that indie-pop can still be useful without descending into pure farce right down your throat. Polair ventures into familiar, yet perilous, territory—that of sparkling lightness—and emerges triumphant.

On paper, it’s the kind of song that would send any discerning music lover running for the hills: tinkling ukuleles, handclaps for rhythm. It sounds like the soundtrack to a Greek yogurt commercial. Except it’s not.

Instead, it grabs you, hooks you, and sticks to your eardrum without ever making you want to rinse your ears with bleach. A summery riff, like a perfectly placed sunburn, and just like that, it’s sold.

Experiment: The Long Echo of a Question

Experiment arrives with a curious, almost spectral weight, a melody from the early 2000s finally given voice in 2024, like a faded letter found in an old coat asking a forgotten question.

The song unfurls with an immediate, tactile mood, its opening arpeggios and bassline draped in the shadow of The Cure’s Pornography era, inhabiting that atmospheric melancholy of quiet introspection.

introspection.

Then, a jolt: the chorus erupts in a Pixies-esque swirl of raw, distorted energy, where Polair’s vocal delivers the core, “Life’s an Experiment,” a declaration born of pain and struggle, yet tinged with the heart’s own unpredictable lurch into vulnerable acceptance.

Lyrically, it traces a familiar arc of searching—”getting lost on side paths / Lingering in the dark”—with a quiet confession of past shadows, culminating in the aching question, “Can I finally find myself back?”.

When the chorus returns, “And I feel I’m coming home” is a fragile sigh of relief, immediately undercut by a cascade of doubt, “Is it real? Is all the testing now behind me? / Is it all done?”, a beautifully human moment where peace remains provisional, the hard-won wisdom of “One day you fall, the next you float” a whispered truth.

Even as new influences enter—a “conversation divine divine”—the “terror to confine” of old anxieties lingers, a recognition that light enters, but ghosts remain. Ultimately, Experiment leans into the transformative power of connection, moving from “Self-isolation and exile” to the “beautiful soul” that “completes me and redefines me,” a hopeful resolution after a long flight, settling on the quiet, uncertain comfort of finding an answer in another.